- Home

- Mindy Schneider

Not a Happy Camper Page 2

Not a Happy Camper Read online

Page 2

“He told you about those, too?” newcomer Betty Gilbert asked. Betty had filled an entire cubbyhole with books. I figured she either read a lot or she’d flunked a class in school and had to make it up over the summer.

Dana Bleckman, back for her fifth season, filled us in on the camp’s owner. “Okay, there’s one thing you need to know about Saul,” she said, laughing. “He’s a big fat liar. Everything he says is a lie. There’s no paneled, heated bunks, no fruit cart that comes around before bedtime, no private camp-owned hydroplane. And just ask Max Peretz—who showed up for his first summer with a brand new set of clubs—no Camp Kin-A-Hurra nine-hole golf course.”

“What about Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan?” I asked.

“Sorry,” Dana said. “They were never counselors here.”

“That’s a new one,” piped in the other returning camper, the hip, hot pants-wearing Autumn Evening Schwartz.

“No, he tried that one on me, too,” Dana continued. “Said Golda Meir ran Girls’ Side and Moshe Dayan taught archery. Like anyone would buy that.”

Actually, I had. It explained Mr. Dayan’s eye and all. I glanced over at the third new girl in my bunk, Hallie Susser, and the look on her face told me she’d believed it, too.

The conversation shifted when Dana did something I could only dream of doing; she pulled out a guitar and started to play. Dana was one of those people a summer camp can’t exist without. A singer and a composer, she had even performed on TV, although it was only UHF. Dana strummed a few chords and hummed softly while the rest of us pulled everything back out of our cubbyholes, looking for pajamas. Talented and beautiful, Dana was pretty much what I wished I was and feared—okay, knew—I wasn’t. One of those girls who always got a boyfriend.

That night, before bed, I wanted to use the bathroom and brush my teeth before climbing into my cot under the scratchy green wool army surplus blankets my mother had taken to her summer camp thirty years before. One little problem. The toilet in our bunk wasn’t working. “Find your raincoats and your flashlights, girls,” Maddy instructed us after inspecting the unusable facility. “We’ll try the bunk next door.”

Maddy had spent fifteen of her twenty summers here and refused to speak ill of her distant relative. Whenever someone questioned her about Saul’s fantastic stories and outrageous claims, she got this sort of faraway glazed look in her eyes, like she couldn’t see or hear what you were saying. Maddy was studying Classics at Amherst College, but her real goal in life was keeping off the weight she’d recently lost. During the spring semester she’d contracted dysentery which she described as “the best disease I ever had” and dropped twenty-two pounds. Now, at five-six and one hundred-five pounds, she was way too thin which, in her mind, equaled good. To keep the weight off, Maddy had come to camp with a little brown suitcase filled with the staples of her new diet. I peeked in once.

“That’s what you eat?” I asked her. “Pep-O-Mint Lifesavers and salted soybeans?”

“I exercise, too,” was all Maddy said, closing the lid as if she feared I might steal her stash.

A seasoned camper, Maddy had also brought along several extra rain ponchos and flashlights, as she had a tendency to lose these items and both were crucial to a summer at Kin-A-Hurra. Apparently, summer was the official rainy season in this part of Maine, along with spring and fall. In the winter it just snowed.

Now, she led us out the front door and into the downpour on an expedition to Bunk One. Their plumbing was broken as well.

“We were planning on coming to your bunk,” one of the girls informed us.

“This is a disaster,” my bunkmate Betty groaned.

Yes, it was, one that I wouldn’t write home to my parents about because I was sure they’d somehow blame me.

“The toilets at Cicada always worked,” I was certain they’d write back.

“Let’s try another bunk,” Maddy suggested.

Sometimes the nice thing about being in a disaster is not being in it alone. Campers and counselors from several other bunks joined our group and we became one massive horde of rubberized yellow trudging around in the mud. We learned that none of the bunks had working facilities. Our only hope was the girls’ dining hall, The Point.

Built on a peninsula jutting out into the middle of the lake, The Point had been built in 1907, back when this property had been a hunting lodge. A truly beautiful building, it featured peg-and-groove hardwood floors, knotty pine paneling and a massive stone fireplace. And the original overhead pull-chain toilets, but at least they were working. There were three bathroom stalls and eighty-five of us. After waiting in the hallway for half an hour, and learning the words to an uncomplimentary camp song, I decided I could hold off using the bathroom until morning, a skill that would serve me well for the remainder of the summer.

Just outside The Point, a cluster of girls stood by the shore, watching a structure across the lake, over on Boys’ Side, go up in flames in spite of the inclement weather.

I feared it was one of the bunks. Specifically, I feared it was the thirteen-year-old boys’ bunk and that someone would die. The boy who was perfect for me, the one I was supposed to date. The one I was supposed to marry in ten years. I hadn’t even met him yet and now everything was ruined.

The blare of the fire engine’s siren echoed across the lake.

“Oh my God! The whole camp’s burning down!” one girl cried out.

“No, I think it’s just a bunk. Hope no one’s inside,” another girl said.

“Looks like the Wolverines’ bunk,” someone else called out as the fire department’s truck roared into view.

“How old are the Wolverines?” I asked.

“Eleven and twelve,” came the answer. “Why?”

“Uh—no reason,” I insisted.

I stood with the other girls and watched as the fire was put out, but my mind was already leaping ahead to the next catastrophe. We’d just lost the plumbing. Would the electricity go out, too? And if so, would my flashlight batteries last eight weeks? And if not—wait—that could be a good thing. I knew all about the days before electricity. I could show everyone how to survive this summer. I could demonstrate how to dip wicks into hot wax and maybe everyone would think I was really cool. Maybe this would be my road to my salvation, my path to popularity.

Maybe this was how I’d get a boyfriend.

Or maybe everyone would think I was just some oddball who knew way too much about candles.

to the tune of

O Come, All Ye Faithful

“O come to Kin-A-Hurra

Come get hepatitis

Mononucleosis and diarrhea, too

Come if you’re nuts

Come if you’re a klutz

The summer will go by

As fast as turtles fly

We’ll be here ’til we die

Saul, why’re we here?”

2

AT MY OLD CAMP, CAMP CICADA, THE THIRD PERIOD OF EACH DAY WAS reserved for General Swim. I hated General Swim. The Girls’ Waterfront was marked off in four sections: Sharks, Perch, Minnows and Guppies. Most of the girls in my bunk were Sharks, having passed their deepwater tests. I was a Minnow, a twelve-year-old minnow, which wouldn’t have been so bad if you didn’t have to have a buddy, but you did, so I’d usually end up partnered with a six-year-old. You know that guy who said it’s good to be a big fish in a small pond? I hated that guy almost as much as I hated General Swim.

The Camp Cicada Girls’ Head Counselor would wake us up every morning by playing a 45rpm recording of Reveille on a public address system. Then he would tell us the weather forecast and what we should wear to breakfast and pretty much everything else we’d be doing that day, each period demarcated by more recordings of Army drill music as we lined up in front of our bunks and then marched single-file to our next fun-filled activity. The camp had drawn up the schedule around 1952 and I’m pretty sure they never strayed. Even when it rained and we stayed indoors, they barked out orders over the p.a.

system: now you’ll write letters, now you’ll wash the toilets, now you’ll have quiet time...

The only thing we got to decide for ourselves was the order in which we’d shower each evening before dinner. As soon as we awakened to Reveille, girls would pop up out of bed and shout, “First shower!” “Second shower!” etc., until everyone had a place in line, except me. I was always last because I never had the nerve to jump in and call out a number. I hoped things would be different—or at least I would be different—at Camp Kin-A-Hurra.

“This is not what I expected!”

That’s what Betty Gilbert yelled out in her sleep and that’s what I awoke to my first morning at camp.

“A sleep-talker! I love it!” whispered Autumn Evening Schwartz, awake now in her bed, two feet from mine.

There were six little army cots in our bunk, three on each side. We slept with our heads up against the wall, feet pointing towards the aisle. I would have expected our counselor to take a bed at the back of the bunk, for privacy. When I looked over, I knew why she’d selected the one closest to the door. It was empty. Maddy had escaped in the middle of the night.

“You guys up?” It was Dana Bleckman. She stretched and took the ponytail holder out of her hair.

“Where’s Maddy? I asked. “Think she went home?”

“Nah. Her stuff is still here. Maybe she went to The Point to use the bathroom. Maybe she’ll meet us at breakfast.”

“What do we do after breakfast?” asked Hallie, who slept across the aisle from me.

“We come back to the bunk,” Dana answered.

“And then what?” I asked. “Clean the bunk? Sweep the floor? What’s the schedule?”

“Schedule?” Dana laughed. “We eat, we do stuff, we eat some more, we do some more stuff.”

Autumn Evening yawned, “Like that.”

Betty Gilbert opened her eyes. “Could you guys keep it down? I’m trying to sleep.”

For the first two days we sat indoors, reading comic books and playing jacks, as we listened to Top Forty hits on local radio station WSKW in Skowhegan. My father believed in library books and did not permit my brothers and me to spend our money on comics and magazines. At Camp Cicada, the other girls had them, but when I asked to borrow one, the snooty response I got was, “And what will you give me?” It’s not that the girls at Cicada didn’t like me, or that they didn’t like me for any good reason. It’s just that I wasn’t born and bred on Long Island like they were. I was an illegal alien and they refused to stamp my passport.

“Hey, wanna read my Archie Joke Book?” Dana asked, tossing it my way. Here, at last, I had my chance to catch up with the kids at Riverdale High, to read the latest movie spoof in Mad Magazine and to ogle open-shirt photos of Tony DeFranco in Tiger Beat. You’d think I couldn’t ask for more, but then I did.

“What do we do when the rain stops?”

Autumn Evening thought a moment. “Um... this.”

“That’s not true,” said Dana. “Sometimes we sit outside and read. And sometimes we go down to the beach.”

It was so random and so free, and it seemed like everybody knew it. At other camps, we knew what we were supposed to be doing: the hours and hours of kickball, tennis and swim instruction complemented by yarn crafts and nature walks and daily bunk inspections where neatness counted. But the schedule at Kin-AHurra was more like this: do anything you want any time you want, unless you just want to do nothing. And so this was how the days were passed, except that the older girls also smoked cigarettes. In my search to find the perfect camp, I had landed instead at the anti-camp.

It was easy to like Kin-A-Hurra, if not for what it did have, then for what it didn’t. For instance, there was no public address system. In its place was an old ship’s bell hanging from a decrepit flagpole. (The idea was to raise the American, Canadian and Israeli flags, but so far we hadn’t raised anything due to the rain.) Our dedicated Head Counselor, Wendy Katz, rang that bell every hour even though we never changed activities and there was no real need for her to keep getting wet. The old wooden bunks had sheet-metal roofs and the sound of the rain pounding down on them was almost deafening, but in a pleasant, reassuring way. On the hour, the conversation would become, “Was that the bell?” “Did you hear the bell?” “What time is it?” Somehow we always knew when it was time for a meal and we’d take a break from our minimal activity and head down to the dining hall.

The Point possessed a grace and serenity the rest of camp lacked. It was the one dry place where all of Girls’ Side regularly assembled and our high-pitched voices sweetly filled the oversized lodge. This was most evident when we sang the blessing over the food, in Hebrew, before meals. I made it a habit to keep my voice low and listen to how perfect and harmonious everyone else sounded together.

Back home, we never thanked God before a meal. We never even thanked my mother. We just ate. Though my father was religious, he allowed us to sit down at the table and plow through the meal as fast as we could in order to get back to watching TV. My parents, seated at the two heads, rarely noticed just how quickly we ate. My father was absorbed in The New York Times crossword puzzle and my mother flipped through House Beautiful magazine. My three brothers and I were seated in between them on both sides of the table, squeezed together to make room for their reading material.

The one exception was Thanksgiving, which was always held at Aunt Judy’s house in Jericho, Long Island, though not actually on Thanksgiving Day. Our family celebrated Thanksgiving the Saturday before because there was less traffic. As Uncle Hank finished carving the turkey with the electric knife he’d gotten from S&H Green Stamps, someone from my mother’s side would shout out, “We forgot to make a blessing!” and we’d hurriedly say one, as if we feared God might be doing a spot check.

Meanwhile, Uncle Hank prattled on, showing off his vast knowledge of wine, which was meaningless to me as my entire frame of reference consisted of the words Manischewitz and Concord Grape. “Here, Tom,” he said one time. (He called me Tom because I was a tomboy.) “Try this,” and then laughed as I nearly gagged on his latest overpriced Merlot.

Thanksgiving at the relatives’ was one of the few occasions when we ate out. My mother didn’t like restaurants. She didn’t like having to sit and wait. “If we were at home, we’d be done by now,” she’d say impatiently, and then scold us for filling up on bread. My mother preferred to make the food herself and then act annoyed if my brothers and I didn’t want to eat it. Once a month she’d make breaded flounder and once a month I’d practically cry, telling her how much I detested it. “Just eat it this once and I’ll never make it again,” my mother would tell me. I fell for that line for seventeen years.

“Ooh! Howard Johnson’s! Can we stop there?” Howard Johnson’s was the one restaurant my parents liked, bland and consistent with prompt service. Everyone but Jay loved to stop for food on the road. Lucky for me, both my mother and father had a sweet tooth and we especially enjoyed the ice cream sundaes, despite their shallow convex metal dishes, served with a little cookie on the side.

“No whipped cream or cherry on mine,” my mother would tell the waitress. “I’m on a diet.” My mother thought this was funny every single time.

Sometimes when we were on vacation we’d go to HoJo’s for dinner and my father would let us order the Tom Turkey entrée from the children’s menu, as if eating non-kosher turkey was somehow all right if it came with a paper placemat and crayons. But when we ate dinner there, we couldn’t have sundaes for dessert. It isn’t permissible to mix milk and meat and we’d have to settle for orange sherbet. That came with a little cookie, too, but it just wasn’t the same. On very rare and fancy occasions we ate at Larry’s Kosher Deli in Plainfield, New Jersey. When I was three years old and we went to the New York World’s Fair, we brought our own tuna sandwiches from home. We never went to McDonald’s. My father believed keeping kosher was an honor bestowed upon the Chosen People and my mother felt it was a worthy tradition, a way to acknowledge o

ur ancestors. But to me it was a burden, something that set me apart from my peers and held me back, although the thought of eating any part of a pig still kind of grossed me out.

At Kin-A-Hurra, all of the meals for Girls’ Side were prepared on Boys’ Side, then trucked around the lake to be vaguely re-heated, and they tasted like it. Still, I enjoyed eating in The Point. There was no need to impress anyone, no risk of being rejected. The Point was safe, our own private girls’ world, no boys to worry about. And yet, I wasn’t getting any younger...

Following three days of heavy rain, the weather cleared and it was finally time to go to the other side of the lake, to meet our counterparts, the Foxes. The boys. While the girls of Kin-A-Hurra may not have followed a set daily schedule, we most definitely had specific goals to achieve by summer’s end. For the youngest campers, the nine-and-under crowd, this meant overcoming homesickness and learning to act casual when letters and packages arrived; for the ten and eleven-year-olds, it was taking advantage of being away and selecting your own candy bars at the store or seeing who could make the most macramé bracelets; and for the twelve-year-olds it was all about looking good, about borrowing clothing and accessories from your friends and learning to blow-dry your hair straight despite the humidity because once you turned thirteen, it was all about the boys.

I was thirteen. I didn’t have to learn how to build a fire or construct an elaborate “God’s eye” from yarn and twigs. The only thing I really had to do was get a boyfriend so I could have someone to say good-bye to at the end. Someone to kiss good-bye. That was really what this summer was about, getting that first kiss by the last night of camp.

We had an hour after dinner to get ready for the trip across the lake. Back at the bunk, Autumn Evening pulled on super-wide bellbottom jeans, a peasant blouse and a kerchief around her head that made her look like “Rhoda.” Autumn Evening was smart and cool and studied Jewish mysticism (whatever that was) along with all other forms of spirituality. She had tarot cards and a Ouija board and claimed she could get in touch with dead campers from the 1920s. I just wanted to connect with one of those still breathing across the lake.

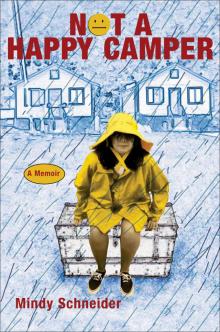

Not a Happy Camper

Not a Happy Camper